Guix Introduction Part 1: Motivation and What Guix Promises

Contents

This is the first part of a brief introduction to the Guix functional package manager, and how it could be used to manage dependencies of projects, much like virtual environments for Python, but with much larger scope.

This is written in a way that I wish Guix was introduced to me back when I first learned it. We first look at the basic concepts related to dependencies, then the motivation of better dependency management, namely the dependency hell, and the desire for reproducible builds. Then we list what Guix promises.

Basic concepts of packages and dependency

We first list out some concepts related to packages and dependency.

Package

- loosely speaking, a package is a collection of functionality that we are interested in, e.g.

Package building

- the final files in a package are often produced through a building process from some sort of source files

- e.g.

ripgrepis written in the Rust programming language, and would need a Rust compiler to produce the program- some pdf documentations may be produced through the Latex typesetting system

- an R package needs to be built, see https://bookdown.org/rdpeng/RProgDA/building-r-packages.html

- some packages are very flexible, and allow specifying different options when building, resulting in functionally slightly different packages

- e.g. some functions may be left out if it is considered not useful

- e.g. some functions could be provided by different dependent packages

- building script:

- most packages have some building process (e.g. a script or a makefile)

- building environment:

- some packages will automatically detect its environment to change building options

- e.g. if some other package is absent, some functionality will be left out, but the building will still succeed

- therefore, if the building environment is not properly isolated, the “same” building script may still result in different built package, depending on what other packages are present in the system

- this is similar to programming where the output of a “function” depends not only on its inputs, but also on other global variables

Package version

- strictly speaking, package version is just a name attached to a package, and the name could theoretically be arbitrary, although most package authors follow some conventions

- e.g. a lot of packages follow the Semantic versioning, briefly

- a version number consists of three numbers, in the format of “MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH”, e.g. “1.0.4”, where each should be incremented as follows

- MAJOR: when you make incompatible API changes, where MINOR and PATCH could be reset to 0, e.g. from “1.2.3” to “2.0.0”

- MINOR: when you add functionality in a backwards compatible manner, where PATCH could be reset to 0, e.g. from “1.2.3” to “1.3.0”

- PATCH: when you make backwards compatible bug fixes, e.g. from “1.2.3” to “1.2.4”

- a version number consists of three numbers, in the format of “MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH”, e.g. “1.0.4”, where each should be incremented as follows

- NOTE:

- normally, different versions will have some differences, although the differences may be small, or supposed to be backward compatible.

- even for the same version number, the package may be functionally different if built differently, as mentioned above.

Dependency

- loosely speaking, if a package A needs another package B to provide some functionality, then A depends on B, i.e. B is a dependency of A.

Direct/indirect dependency

- often a package will list out its needed dependencies (possibly also the range of allowed versions of each dependency), either formally in some fixed format, or informally as free text in some readme

- direct dependency: the dependencies listed for a package

- indirect dependency: not direct dependency, but are (direct or indirect) dependencies of the direct dependencies

- Why the distinction of direct and indirect dependency? Both are needed to fully capture the dependencies.

- the distinction is useful mainly when the dependencies are updated

- if package A directly depends on package B, presumably the developers of A knows which functionality of B is needed

- if B is updated to B1, then the developers of A need only check whether the needed functionality is still provided by B1, and act accordingly, rather than checking each of the dependencies of B and B1 to see which are still needed.

Build-time/run-time dependency

- build-time dependency: dependency needed for building a package

- e.g. a particular version of

gccfor compiling a program - e,g, statically linked libraries, i.e. those compiled into the program, so are needed at build-time

- a build-time dependency may or may not be needed when the program is later run

- e.g. a particular version of

- run-time dependency: dependency needed for using the package, e.g. running the application

- e.g. the dynamically linked libraries, i.e. the libraries will be loaded only when the program is run

- nowadays, most programs use mostly dynamically linked libraries

- NOTE: a dependency can be both build-time and run-time dependency

Optional dependency

- optional dependency: dependency that can be omitted for the package to build or run, but some functionality may be missing

- e.g. inkscape can be built without the optional dependency

potrace, just without bitmap tracing functionality. - in most package managers which mainly distribute binary packages, often most optional dependencies would be included to provide the most functionality

Dependency hell

- roughly speaking, dependency hell refers to the problems caused by the dependency on specific versions of some packages.

- dependency hell takes a few forms:

- too many or long chains of dependencies:

- this is only a problem if the dependencies have to be hunted down manually, which could become tedious very quickly

- most package managers solve this by installing the dependencies when a package is installed

- conflicting dependencies:

-

in many package manager (and default in dynamic library in Linux), minor versions are considered backward compatible, and for each package of the same major version, only the newest minor version is kept/used

-

if both package A and B depend on a package C, but A and B needs different minor versions of C to work correctly, then A and B have conflicts

-

this may happen if B is updated to B1 causing C to be updated to C1, therefore causing A to break, even if the older versions of the 3 packages previously coexisted and worked correctly.

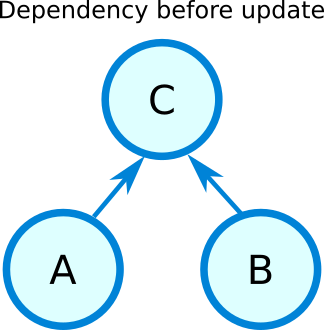

Figure 1: Dependency before updating B

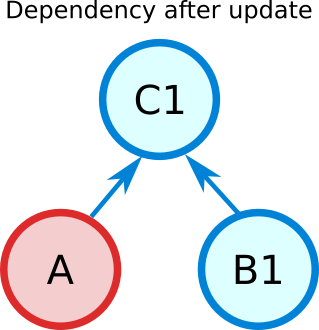

Figure 2: Dependency after updating B

-

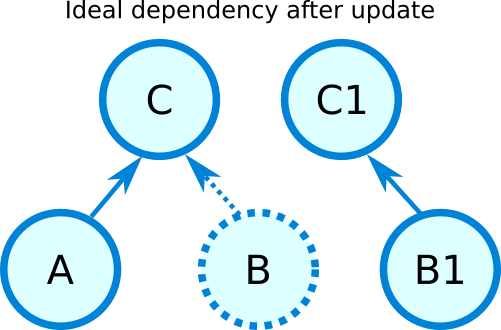

in this case, it is clear that if we just let A use the old C, and let the new B1 use the new C1, then A can work as before, and B can still be updated to B1.

Figure 3: Ideal dependency after updating B

-

- too many or long chains of dependencies:

- ways that code of package A can break if a dependency B updates to a supposedly backward compatible minor version:

- although most of the time updating a minor version does not cause problem, they might still cause breakage

- e.g. suppose A depends on a function in B, there could be a few cases:

- the function interface remains unchanged or adds optional parameters, but the implementation is changed:

- A may rely on undocumented behavior of the function, which has changed in the new implementation, although the documented interface is still the same.

- e.g. the old implementation may sort the output as a side effect, but not promised in the function interface, and A may have relied on the sorted order

- the new implementation may have buggy edge case, causing A to break

- the new implementation may expose a buggy edge case in A, causing A to break

- A may rely on undocumented behavior of the function, which has changed in the new implementation, although the documented interface is still the same.

- the function interface remains unchanged or adds optional parameters, but the implementation is changed:

Reproducible build

- it is desirable to have the exact same versions of dependencies between testing and production systems, and preferably also for the development environment

- it is therefore desirable to reproduce the exact same set of packages on a different machine (of the same architecture) and/or at a different time

- this could be achieved in two main ways:

- record the set of versions of the (pre-built) packages, and reinstall when needed

- e.g. python virtual environment mostly follows this paradigm

- record the set of versions of the packages, and rebuild them when needed

- this is similar to the previous one, with the difference that the package can be built from scratch if needed

- e.g. Guix can rebuild package(s) through the set of package definitions with explicit dependencies information

- Guix can simply download the pre-built package (called substitute in Guix) when available

- record the set of built packages and just copy them as a whole when needed

- e.g. building a docker image to contain all needed packages

- record the set of versions of the (pre-built) packages, and reinstall when needed

- isolated building environment can help with reproducibility

- only the explicitly listed dependencies are visible in building, so that the building script will not depend on other packages unknowingly

- reproducibility raises the question of sameness of packages

- the package name with version number would be sufficient if each version is always built in the same way with the same versions of dependencies

- this is the strategy adopted by most package managers

- a better way is to use the package name together with some kind of hash

- not necessarily the hash of the package itself, as we will see in later parts of this series

- but different contents of a package should produce different hashes

- the package name with version number would be sufficient if each version is always built in the same way with the same versions of dependencies

Hash

- basically a (very large) integer calculated through a hash function on some input, e.g. a file

- the calculated integer is in some fixed range, often written as a long hexadecimal string such as “730e109bd7a8a32b1cb9d9a09aa2325d2430587ddbc0c38bad911525”

- the input however often has no length limit

- e.g. sha-256, md5

- desired properties of a good hash function:

- the same input always produces the same hash, i.e. it is a pure function in the mathematical sense

- i.e. if two inputs produce different hashes, the two inputs must be different

- it is one-way

- there is no efficient way to recover the original content just from the hash, other than trying all possible inputs to find those that give the same hash

- even a slight change in the input results in drastically different hash

- useful for identifying corruption or tampering of files

- can record the hashes of files, then calculate again at a later time, or after the files are transferred to a different machine, to check that the files still produce the same hashes. If not, the file is definitely different.

- low collision, i.e. different inputs should produce different hashes

- it is impossible to have no collisions unless the set of possible inputs is less than the set of possible outputs

- so the realistic hope is that when used on the set of common real world inputs, there are no collisions

- the same input always produces the same hash, i.e. it is a pure function in the mathematical sense

- note that one hash is enough to represent a web of connected things:

- e.g.

- if you have a few (ordered) inputs, you hash each of them, and write the hashes to a file, then you hash this file

- this is still a deterministic hashing process

- if any of the input is changed, its calculated hash will most probably be different, so this file of hashes will be different, and consequently the final hash will be different

- each of the input itself could contain hashes of more inputs recursively, so a web of things could be represented as one hash

- this technique is also used in git version control system to link the commits together

- the same technique could be used to hash the (direct) dependencies of a package, and therefore one hash could represent all the direct and indirect dependencies of a package

- e.g.

Guix: functional package manager

Guix has the following characteristics:

- Guix is in fact a package building system, being a good package manager is a side effect

- designed to properly address the “dependency hell” problem

- aims at reproducible builds

- the exact same set of packages could be reproduced at a later time or on a different machine (of the same architecture), by just using two small text files

- allows atomic installation/uninstallation/upgrade of packages

- each action may involve one or more packages, and is a transaction, i.e. either it succeeds as a whole, or does not succeed, there would not be half installed packages

- allows easy rollback of install/uninstall/upgrade actions

- each transaction results in new generation, which is like a snapshot of the current set of packages (in a profile)

- can easily rollback to previous generations

- so there is little fear of accidentally installing/uninstalling/upgrading the wrong packages

- allows different versions of the “same” package to coexist and used by different packages, without conflict

- encourages declarative package management

- a set of packages can be specified in a manifest file, and can be installed in one transaction

- currently only works on GNU/Linux

- can be installed on any GNU/Linux distribution such as Debian, Ubuntu, Arch, etc

- can coexist with the existing package manager of the distribution

- allows each user to manage his/her own packages

- without root privilege

- without interfering other users

- each user can have multiple profiles of packages

- each profile has its own list of generations, and can be rolled back separately

- allows easy creation of isolated environments with designated packages

- useful for per-project dependency management

- Guix system is a GNU/Linux distribution built on top of the Guix package manager

- uses a config file to declaratively specify the whole system, e.g. the system services, user accounts, etc

What’s next?

At this point, you may not think these characteristics are special if you have not experienced the pains brought by dependency management. Hopefully after reading this series of posts you will have better appreciation of why a package manager is useful and why Guix is a good one due to these good characteristics.

In this first part we looked at the motivation of better dependency management, and listed what Guix promises. Next time we will take a closer look at Guix, and discuss the various components of Guix.

Author Peter Lo

LastMod 2021-05-01